Born in Peoria, Illinois, Mary Turner Salter went to high school just across the Mississippi River in Burlington, Iowa, before moving east to study music at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. She was a gifted mezzo-soprano and pianist, and she sang professionally in Boston and New York City and taught voice at Wellesley College from 1879 to 1881.

She stopped teaching after marrying Sumner Salter, organist and director of music at Williams College—but at the same time she began composing. Their partnership was a creative boon for her: she and her husband would play piano duets for hours together, and he championed her compositional efforts, often helping her prepare her works for publication. In a 1919 interview she said that he “has been the inspiration for my best songs. We sang in the church choir together before we were married. My first song was dedicated to him, although he would not then let me write his whole name on it, but only the initials ’To S.S.’ No one ever had such good time doing things as I do, it is such fun!”

Salter composed over 200 songs, many to her own poems. They are written in the “parlor”-music style that was immensely popular in the late 19th and early 20th century; these are songs that were designed for use and enjoyment in domestic spaces, often with amateur musicians in mind. But they are far from simplistic. Salter’s songs have beautiful, singable melodies that fluctuate with the shifting moods of the poetry. (She attributed her strong sense of melody to the fact that she “sang much as a girl, and now sing inwardly. Melody holds one so.”) And they are full of expressive chromaticism and magical harmonic twists. Her songs are models of nuance and craft, and they deserve to be heard more widely. The four recordings below were created especially for Art Song Augmented by soprano Camille Ortiz, pianist Gustavo Castro, and recording engineer Joseph Wenda; they are the first professional recordings of these songs.

Additional Resources

Precious little has been written about Mary Turner Salter, but here are a few places to go to learn more about her and her music.

- Kinskella, Hazel Gertrude. “How Mary Turner Salter Composes Her Songs.” Musical America. March 1, 1919.

- “Mary Turner Salter.” Brief biography from the University of Colorado Boulder Library (“Some Women of the AMRC Digital Sheet Music Collection”).

- Wilson Kimber, Marian. “Listening to Loss in ‘The Cry of Rachel.’” Women’s Song Forum. March 27, 2021.

- Mary Turner Salter’s obituary, from September 1938.

- My podcast episode about Salter’s “Afterglow.”

Analytical Notes

Here are some analytical observations about one of the songs featured below. My hope is that these comments will be useful to those who would like to use Salter’s songs in the classroom, the private studio, or the recital hall.

“Afterglow”

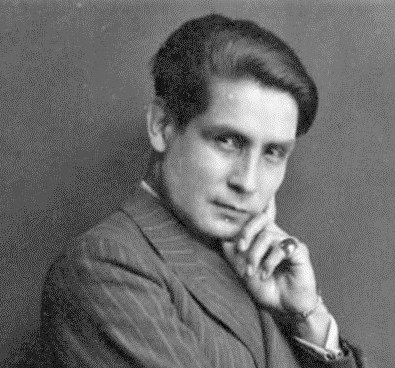

The first song in the video below—“Afterglow,” published in 1908—is a true gem. It’s a setting of a poem by the American poet, literary critic, and translator Thomas Walsh (1875–1928), who published four books of poetry between 1905 and 1920. This poem was published in a 1909 book, but Mary Turner Salter would have discovered it a year earlier, when it was printed in Harper’s Magazine. Walsh’s poem is only four lines long, and on first glance it may seem no more than a trifle—simple, with a predictable meter and rhyme scheme; pastoral; a touch sentimental. It captures an evening scene, when the sun has just set and everyone is coming home after working in the fields:

Over the orchard one great star;

The mellow moon—; and the harvest done;

And the cheek of the river crimsoned far

From the kiss of the vanished sun.

The outward simplicity, however, conceals an inner subtlety. The poem conveys so many sensations in such a small space: awe, fatigue, a touch of nostalgia, the feeling that time passes inexorably even as we long for it to stop. The motion of the four lines—at first hovering and lingering, thanks to all the semi-colons, and then moving ahead in two lines that have no punctuation—mirrors the motion of the objects in the scene. The star and the moon hang motionless in the evening sky; then the river flows onward and the sun sinks below the horizon. The poem, in short, may be a suspended moment, but it’s a moment that breathes—or that holds its breath and then exhales.

Mary Turner Salter’s song expresses all these sensations, and then some, in just 25 measures. (You can find a copy of the score here.) Notice, for example, the shape of the opening melody (“Over the orchard one great star”). The melody rises, mimicking the gaze of the poetic speaker as she looks upward, and then lingers on the crucial word “star”; Salter makes it the focal point in the line just as it’s the focal point in the sky. And she inserts a small gap between the words “orchard” and “one,” as though the sight of the star has taken taken the speaker’s breath away.

The harmonies also paint the scene beautifully. The song begins simply enough, with just a touch of chromaticism, but the harmonies darken as the song goes, culminating in the flat-side chords beneath the dramatic high Fs on “crimsoned FAR,” “from the KISS,” and then the repetition of “the KISS.” The two “kiss” chords are D-flat major and B-flat major, as far from the D-major tonic as the river is from the sun that has disappeared below the horizon. (Amazingly, the only root-position tonic in the song is the final chord.) The distance feels all the greater because Salter dwells on these chords, the pianist arpeggiating upward into sustained dotted half notes and the singer floating above. If the last two lines of Walsh’s poem flow on, Salter’s setting of the lines holds back, not wanting to let go of the blissful moment.